The Providence-Memphis Connection

Chris Armentano contributed this article to Friar Basketball on Providence, Memphis, and the impact of their basketball programs in 1973 — and beyond. I hope you enjoy this look back as much as I did.

Providence and Memphis. Most people never mention these two remarkable cities in the same breath.

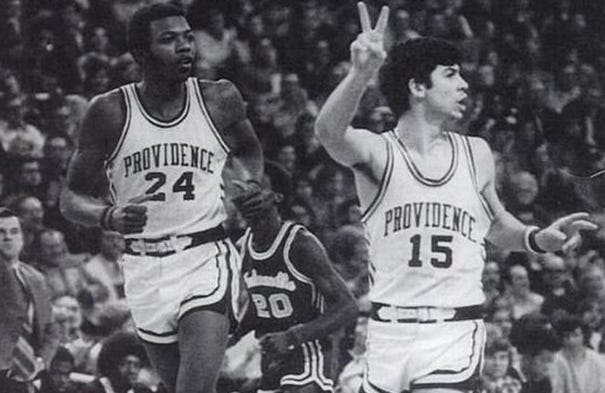

Unless, of course, they’re old-time fans who recall one Saturday in 1973 when the Memphis State Tigers defeated the Providence College Friars in the NCAA Tournament semifinals. The Friars, led by hometown heroes Ernie DiGregorio and Marvin Barnes, boasted the best lineup in team history. Diehard Friars fans forever describe this game as the one that got away: a could-have, should-have win that still haunts their basketball memories.

1973 was a tumultuous year when the Vietnam War, Watergate scandals, and civil rights struggles all took center stage.

By then racial conflict had touched most American cities, north and south of the Mason-Dixon line. In the mid-60's a University of Rhode Island survey found Providence “as segregated as many cities in the deep south.” A riot in ‘67 led Providence Mayor Doorley to prohibit large gatherings and institute a curfew in South Providence. In 1971, the freshly-integrated Central High closed for a week after conflict erupted between Black and White students.

While Providence was on the periphery of the Civil Rights Movement, Memphis was at Ground Zero. In April, 1968 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated as he stood on the balcony of the city’s Lorraine Motel. He had come to Memphis to help settle a strike by sanitation workers whose modest demands for fair treatment were thwarted by Mayor Henry Loeb. Loeb, a Brown University graduate, had his own Providence connection.

According to Elvis’s eye doctor, Dr. David Meyer, King’s death caused immense sadness in the Black community. Whites, he told me, were both saddened and ashamed.

Eventually, sadness turned to anger and Memphis limped on as a deeply divided city. Blacks and Whites shared little other than deep distrust and animosity.

The struggle to desegregate schools made things worse and the situation seemed hopeless. Then, in 1973, the Memphis State basketball team captured the city’s heart, just as the ‘73 Friars had won the affection of the state of Rhode Island. As engaging as it was, Providence basketball was entertainment. In Memphis, basketball proved to be a lifeline.

I first heard about the impact of the ‘73 Tigers on the city’s deep racial divide from Dr. Luther Ivory, a Memphis native who experienced the traumatic consequences of the era.

While we were discussing the aftermath of the King assassination, I asked him, what, if anything, helped heal the city.

“It’s a funny thing,” he said. “It was 1973…”

He didn’t need to complete the sentence. As a Friars fan, I knew exactly what he was going to say; it was Memphis State’s success on the basketball court that brought the city some relief.

Like the Friars, the Memphis State Tigers were led by two local stars. Larry Finch, a tough-nosed shooting guard, and Ronnie Robinson, a powerful six foot eight rebounder hailed from the city’s proud, but segregated, Orange Mound section. They came from large families of seven and eight children respectively. Each lost his father to an early death, leaving their moms in the role of breadwinner.

As domestics for White families, their mothers earned $5.50 per day, less than minimum wage paid to workers in Southern New England. From that meager pay, fifty cents a day went for the women’s bus fare.

Finch was the first local African-American prep star to play for Memphis State.

Though the team had been integrated since the mid-60s, the school avoided enrolling Black athletes who might out-shine their best White players. Given the school’s past history with Memphis’ best Black players, Finch’s decision to attend State wasn’t popular in his community.

At the start of the 1972-73 basketball season, anger and mistrust still dominated race relations, and white flight resulted in economic decline in the urban core.

It had been that way for nearly five years, but with the growing success of Tigers’ basketball, race relations began to thaw.

Blacks and Whites finally had something in common, something to jointly celebrate that overcame years of hostility. Everyone wanted to be part of it, including stars like Oscar-winner Isaac Hayes and singer Al Green who partied with players and coaches. Even Dr. David Meyer was caught up in the excitement. On one occasion he drove four hundred miles to Tulsa on his own initiative to monitor an injured player.

Some say the city healed. One of those, Zack McMillin, former sports writer for the Memphis Commercial Appeal, claimed that as illogical as it might seem, the team’s success helped dismantle racial barriers.

Others say the effect was temporary. Most Black Memphians that I have spoken to say the myth surrounding the team’s positive impact on race relations is overstated. In their minds, things went back to the way they were.

Nevertheless, most Memphians agree that for a handful of months in 1973, the city was more united than for almost five years. Goodwill and unity peaked during the Final Four.

When the Friars and Memphis State met at Saint Louis in the national semifinals on March 24, 1973, the Friars raced out to an early lead. One legendary coach, Nat Holman, is said to have called it the greatest eight minutes of basketball he’d ever seen. The Friars were firing on all cylinders, with DiGregorio and Barnes leading the way.

When Memphis State called an early timeout, it was clear they couldn’t stop Barnes. The Tigers had to get more physical if they had any chance of slowing him down.

Minutes after play resumed, Barnes, off balance from a poke, fell hard as his knee buckled.

A hobbled Barnes later re-entered the game but was ineffective.

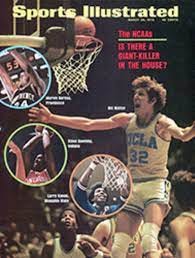

State, of course, went on to win against the Friars, before stumbling against UCLA.

So unmemorable was the game to some Memphis players that Larry Kenon, who went on to star in the NBA, told me he had little memory of their victory against the Friars. Finch was more impressed, especially with Ernie D’s ball handling and one pass in particular: a long, down-court, crowd-erupting, behind-the-back pass to streaking Kevin Stacom.

The Memphis season ended two nights later in the loss to UCLA, a game many Tigers’ faithful think the team could have won had officials more diligently called goal-tending on Bruin’s star Bill Walton.

Walton made twenty-one of twenty-two shots in the UCLA victory which remains an NCAA Tournament best.

Larry Finch, who went on to become the first Black head coach at his alma mater, led the basketball program for eleven years, earning six NCAA Tournament bids and an Elite Eight appearance in 1992. Dexter Reed, a University of Memphis sports hall of famer, told me that Finch's impact was more than victories on the court. “He knew he could win,” said Reed, but getting players college degrees and turning them into good citizens came first. Reed sites himself as a prime example. Long after his playing days were over, Finch pulled him back to school where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees. Reed's gratitude is clear when he says, “He gave me another life.”

Finch, like former Friars' coach Ed Cooley, was a natural ambassador, whose easy manner and palpable optimism, made him loved and admired in his home city.

During his tenure as player, coach, and public figure, some say Finch did more for race relations in Memphis than any other person in the post-King assassination era.

A Memphis historian told me about ten years ago, “There ought to be a statue of Larry in Memphis for all he’s done for the city.” His wish came true forty-eight years after the 72-73 season. In 2021 a bigger-than-life bronze statue of an upward looking Finch about to launch a jump-shot was dedicated on the campus plaza named in his honor.

In February 2023, the Tigers and Friars shared nearly identical basketball records. Both seemed headed for March Madness, with the possibility somewhere along the line of a fiftieth anniversary rematch. In that event Providence-born Coach Cooley would have shared the long court-side benches with Tigers’ Coach Penny Hardaway, a Memphis native and Finch recruit. Just two local men who had made out well, and were representing their cities.

It's not a stretch to say Finch, Hardaway and Cooley (now at Georgetown) are all linked in the history of college basketball to P.C. alumnus John Thompson, who in 1984 became the first Black coach to win a national title. A year later, Arkansas hired Nolan Richardson, the South’s first Black head basketball coach of a major university. The following year Finch took the helm at Memphis.

I’d like to think it was more than Thompson’s on-court successes that helped open opportunities for Black coaches. His determined stands for black athletes, 97% player graduation rate, and unshakable integrity no doubt figured in.

Of the four local heroes: Finch and Robinson from Memphis and DiGregorio and Barnes from Providence, only Ernie D. is still living. As is too often the case, the three others, all Black men, died much too young. Barnes was sixty-two. Finch, sixty and Robinson, fifty-three. This fact, a comment on racial disparities of the past, invites us to be attentive to those that still exist. For no other reason, we owe it to the players who’ve brought us so much joy.

Tremendous article